Art crafts

|

|

|

Traditional crafts are an important facet of a culture reflecting the unique sense of form, aesthetics and craftsmanship of its people. In Korea, however, the traditional crafts began to decline toward the end of the 19th century when Korea opened its door to the onrushing influences of the Western civilization. Western influences brought about sweeping changes in lifestyles and values. With demand for their products declining steeply, many artists and artisans had to hurriedly seek new occupations, threatening the continuation of traditional crafts. In 1962, the government decided that such a grim state of affairs must not continue. Under the law, many traditional handicrafts, music, folk plays, dances and other performing arts were designated as the intangible cultural assets. At the same time efforts were made to locate long-neglected craftsmen as possessors of skills and knowledge in the designated assets. These "living national treasures", as they have become known, have since been provided with direct and indirect government supports so that they can not only carry on their crafts but also train younger apprentices to preserve these traditions.

Wooden craft

Wooden furniture of designs unique to Korea was developed as a result of the sedentary customs of Korea living and sleeping on cushions and mats on the floor. Korean furniture is characterized by simple, sensitive designs, compact forms and practical. Joseon woodcraftsmen were noted for the attention they paid to even the small parts hidden from view and their ingenuity in balancing practicality and beauty. Artisans always strived to achieve pieces that were both sturdy and aesthetically pleasing. The grain and texture of the wood varies according to different decorative element and was presented in a most pleasing arrangement. The wood was polished with oil to maximize the natural effect of the grain of the wood and no paint was applied. Metal hinges and ornaments were used on chest and other wooden furniture not only to reinforce their structure but also to enhance their beauty.

Lacquer ware

The history of lacquer ware inlaid with mother-of-pearl goes back to Silla (BC 57-AD 935). Later, lacquer ware was generally decorated with dainty mother-of-pearl chrysanthemums or other floral patterns in continuous arabesque designs. Tin or bronze wire was used to depict the vines, and sometimes pieces of turtle shell, very thinly sliced and tinted red or yellow, were used for variety. At the end of the Goryeo dynasty (918-1392), the design became bolder and larger, and sometimes rather gross. Peonies, grapes, phoenixes and bamboos took the place of the delicate arabesque patterns. The ten longevity symbols also became quite popular with time and remain so even today.

Mother of Pearl (Jagae)

It is an artwork of inlaying lacquer with mother of pearl. It has been a well-known Korean specialty for centuries and remains a popular luxury item in Korea today. The artwork of Jagae came to Korea in the 7th century from China, when Korea was greatly influenced by the Tang culture. It was more popular during the Goryeo period. Lacquer ware is produced by plastering hemp cloth on wooden charcoal powder and rice glue. When dry, the surface is lacquered and ground repeatedly to obtain a smooth, lustrous surface. The beauty and quality of lacquer is more dependent of the design and on the luster of the shell. Abalone is considered the best for its translucent quality. Lacquer ware furniture, chests, jewelry boxes are among the most popular items.

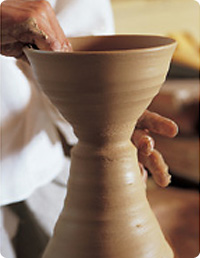

Pottery (Dojagi)

Celadon refers to a type of ceramic made of silica in clay with some iron contents that is shaped into a certain form and coated with glaze containing 2-3% iron before being baked in reducing flame at high temperature. Celadon comes in a wide variety of types with different names according to different materials, decoration techniques, and glazes. Pure celadon, which was the most common type, refers to unpatterned celadon and most incised or raised celadon. Other types of celadon include the iron black decorated celadon, inlaid celadon, white slip decorated celadon, and copper red decorated celadon.

Influenced by the highly developed ceramic arts of China, glazed porcelain and other porcelain ceramics appeared in Silla and developed into an early form of celadon. The early celadon ware of the 11th century, at which time the art had already achieved quite a remarkable level, concentrated on the perfection of forms and a celadon glaze which was bluish green. Floral designs were sometimes engraved or carved in relief on the surface of the pieces which were often made in the shape of man, animals, or fruits.

The technique of inlaying, which is unique to Korea involved incising designs into the clay and adding fillings to smooth away prior to the firing. Inlaid celadon declined from the end of Goryeo through the early Joseon period, gradually giving way to a ware made of the same grayish clay as Goryeo celadon ware but decorated with a method employing white slip called Buncheong, patterns could be inlaid or stamped, painted in iron pigment, or even made by scratching designs into the slip coating on the vessels or cutting away the slip to create a design. Celadon ware, white porcelain and iron-glazed ware continued to be produced when the Buncheong was enjoying its heyday, but from the 17th century onward white porcelain became the most prevalent and was produced in bulk by numerous public and private kilns. At first, it was plain white porcelain ware but soon these began to be decorated with designs of under glaze blue cobalt, copper oxide and iron oxide.

White porcelain ware was produced ardently. Plum tree and bird combinations, landscapes, grapes and grapevines, pine trees, bamboo, and orchids were most often painted on the Joseon white porcelains. All Joseon porcelain wares were noted for the clear luminosity of their whiteness, the simple elegance of the curved forms and the thickness of their walls. Celadon is a type of china which has a mysterious blue color. It is also a kind of industrial art objects demanding high level of skill and precision work. Potters begin by creating a shape out of clay and then imprint on the shape, by means of etching, an inscribed pattern. Then celadon is fired with pine wood for the first time at the temperature of 800 degrees Celsius for 2 days. The second firing takes place for 5 days at 1,300 degrees Celsius after the natural glazes are applied. During this process, the silicon in the clay becomes a silica-compound, adding extraordinary hardness and density to the vessel. In making the celadon, the clay has more iron in it, and the glaze also has two to three percent more iron in it. Celadon is categorized by the techniques and patterns employed in the making-process.

There is celadon, incised celadon, reverse-incised celadon, molded-celadon, iron-painted celadon, patterned celadon, and inlaid celadon. It takes 70 days and 24 stages before the completion of celadon pieces. The creation of Sanggam, an etching method, is one of Korea's technical mysteries which help to make it a priceless treasure unique only to Korea. However there are more damaged pieces. Much to our regret, however, since the late 13th century celadon culture went into a decline and could not be restored with the fall of Goryeo dynasty.

Ox Horn Artwork (Hwagak)

Hwagak is a woodcraft form unique to Korea. It literally means the painting of horn. It is a technique employing ox horn to decorate chests, boxes and small objects for women. It is not known when this technique first came into use, but furniture decorated with ox horn has been popular in the women's living quarter for quite some time for their colorfulness. The use of ox horn is quite reminiscent of Goryeo's penchant for turtle shell. To make a Hwagak piece, horns are boiled to remove the cartilaginous inside and then sliced thin and ironed flat. The horn slices are then polished until they become translucent. Designs are painted on the pieces of horn in bright colors mixed with glue made of ox hide and the pieces of horn are glued on to the wooden surface with the painted side downward. It is inevitable that the durability of an ox horn work is rather limited in a climate of drastic seasonal changes such as Korea. With the development of horn preparations and the improved quality of glues, however, more durable ox horn pieces are expected to emerge in the future.

Ornamental knots (Maedeup)

Ornamental knots were once such an integral part of day-to-day living that government workshops employed artisans to execute such works. Maedeup was used not only for personal accessories such as purses, perfume bags, and belts but also for interior decoration, the decoration of musical instruments and royal sedan chairs among others. It was also utilized in rituals, for example as a symbol of the soul of the deceased. Although this skill originally came from China , it was further developed into a unique system of color and design. Well-made pieces have perfect symmetry and are identical in appearance whether viewed from the front or the back. The making of such pieces involves many steps beginning with the preparation of the cords, upon which the quality of a knotted piece is highly dependent. Raw silk is first cleansed and softened by removing fatty substances and then dyed in various colors. Silk filaments are then twisted together to form long threads. Cords are then made by braiding any number of threads together and the number of threads determines the name of the cord. Once the cords are made, the next is formed by at least three point of contact on a single cord. There are more than 30 different knots that can be combined to form interesting configuration.

Stamps

Most Korean have personal seals safeguarded somewhere in a drawer at home. In Korea seals are often used in place of handwritten signatures. Small wooden or stone stamp used when opening bank accounts or signing official contracts signifies that the owner will take full responsibility for their actions. It is almost like another piece of personal identification, an extension of yourself and your image. Numerous materials are used to make seals, jade, ivory, boxwood trees, bamboo, jujube tree and cherry trees. Carving a seal needs a painstaking amount of effort, as the work entails constructing the symbol of a person. Seeing these pieces of such a poignant art form expressed within the space of less than a square inch, you will be reminded of their importance. Though these small items are fading from the memory of a quickly changing society, the historical and cultural implications of these stamps go beyond our imagination.

Headwear (Gat)

Gat has been the typical and formal attire of upper class man, Yangban, until the late 19th century. The style of gat underwent some changes over the centuries. In the 18th century a very broad rim was popular, ranging from 60-70 cm in width, whereas by the early 20th century, the rim had narrowed to 30cm. There were two kinds of gat, fine or coarse, depending on the material and the skill of the craftsmen. After the brim was woven of hair-like strands of bamboo, a mixture of glue and black ink was applied to hold it together firmly. The brim was then ironed to give it a slight inward curve. The top of the hat was also sometimes made of thin stand of bamboo but it was usually made of horsehair over a wooden form. It was then given several layers of a glue and lacquer mixture to make it stiff.

Yundo

In the Chinese characters which its name is derived, Yun means Wheel and Do means Picture, thus "Picture Wheel ". For centuries it was an essential piece of kit for itinerant monks traversing countryside, sailor out at sea, and geomancers, who relied on its reading to find good spots for building houses or tombs. Usually, made with a round block of wood, a Yundo has a magnetic needle in its center and tiny Chinese characters engraved on its surface in concentric circles. All the characters relate to principals of Yin and Yang, and other ancient metaphysical concepts such as Five Elements, the Eight Trigrams and the Heavenly Stems. Yundo are classified by the number of concentric tiers, they have. This can range from one, which would simply convey directions, to a 36-tier Yundo said to have existed in China. Although Yundo once played a crucial role in the everyday lives of Koreans, today they exist only as a relic of a long-gone culture.

Bamboo crafts

Most prized among the many bamboo crafts are the colored baskets or Chaesang. Such baskets were one of the most coveted articles for young woman's dowry. Famous for excellence in dyeing and weaving, the baskets are usually of two parts - container and lid. In most cases the baskets are produced in sets of three or five, varying in size so that each basket fits inside another for easy storage when not in use. Such sets range from small needlework containers to large garment holders. For extra strength and durability, a basket was encased inside and joined together at the mouth around which wide bamboo bands were placed on the inside and outside and tied together with either cloth or leather and green paper was plastered on the interior. The exterior shell was usually woven with colored and specially treated strips in various patterns, geometric designs, and such Chinese characters as longevity and health.

Fans

Korean fans are of two types, a flat type with a handle and a folding type. Both types are made of thin bamboo strips and covered with Hanji or paper made of mulberry fibers. Fans were usually highly decorated, especially folding fans. The ribs were often painted, colored with ox horn or pink mahogany, or decorated with pyrographic, or burned designs. The natural coloring of the bamboo was also utilized as in the case of the folding fans in which the spots of the bamboo provided the decoration and the name Hapjuk (spotted bamboo). The face of the fans was also decorated with landscapes, flowers, birds, and the Four Gentlemen - plum, iris, chrysanthemum, and bamboo. The most popular flat fans were the Hwangseon fans so named for the yellow color of the oiled paper. Fans in old days were a means of personal adornment as well as a means of covering one's face in a society where segregation of men and women was strictly observed. Fans were traditionally given to court officials by the king during the festival of Dano, the fifth day of the fifth lunar month.

Grass Products

Korea has been primarily agrarian and therefore it is only natural that grass handicrafts flourished. Mats, summer hats, strings, cushions and the like were common items made from grasses. Reeds, arrow-root vines, and straw were often used while sedge and rush were cultivated expressly for such purposes. Most notable among grass products are sedge and rush mats which are suitable for the Ondol or floor heating system that was developed some 2,500 years ago. There are two kinds of sedge mats: one made by plaiting split sedge stems with strings; and the other produced entirely of sedge. Mats are usually 1.2m x 2m or larger and decorated with woven designs of dyed sedge. Favorite designs include clouds, cranes, flowers, birds, tigers, pines, Buddhist swastika, and the Chinese characters for longevity and health. Such designs are also incorporated in smaller mats or Bangsok which are used for individual seating in a square shape, and are made by clothing-spiraling out to the desired size and then inward to the center to form a cushion of two layers. Even better than sedge, rush was another material used for such articles. While sedge requires splitting, rush can be used as in and is also more flexible.

Embroidery (Jasu)

The art of embroidery reached a level of excellence in Goryeo (918-1392), the kingdom that replaced the Unified Silla, as evidenced in many references to embroidery in the History of Goryeo. According to the history books, embroidery on clothing tended to become so extravagant and luxurious that the king often had to put restrictions on the use of embroidery and rich fabrics. There are numerous discussions and illustrations of embroidery techniques and motifs, especially those used for the clothing of royalty. In the court milieu, various kinds of reliquaries and functional objects were decorated with embroidery. Large fans used to protect the king from the wind during processions, Hwagae, a sort of parasol, royal carriages, saddles, drapes and cushions used for departing foreign dignitaries, the tassels on curtains in court assembly halls, and padded linen table cloths, all were embroidered with luxurious yarns and threads in exquisite motifs.

At the beginning of the Joseon dynasty (1392-1910) the court was preoccupied with projects to create and evolve a fresh cultural and artistic environment in conformity with the newly established government. These included the institutionalization of an insignia system in the form of breast patches and the reestablishment of the court controlled handicraft industry. Breast patches indicting the rank and status of all public officials, both civil and military, created a new genre in the history of the Korean embroidery. In a very short time the court-controlled handicraft industry started to boom and was able to produce fine quality products. Embroidery thus became an independent industry which was operated by many craftsmen who produced both woven material and embroidered objects for the court and aristocratic class alike. Court embroidery or Gungsu is characterized by formal composition, high quality craftsmanship, detailed motifs and exuberant style. Minsu style was also developed the embroidery for and by commoners.

The Minsu techniques were handed down from generation to generation, mostly by women. As one person is usually responsible for making an item in its entirety, Minsu works are characterized by expressions of the craftsman's personality and individuality, something that is rarely seen in Gungsu works. Increased public demand for embroidery led to the development of commercial embroidery in the latter part of Joseon. In the last years of the 19th century, almost everything conceivable was covered with embroidery come from this period. They are extremely diversified in kind and in scale ranging from very small functional items, like needle pouches and spoon holders, to large folding screens and wall hangings.

Ornamental knife (Eunjangdo)

They are small enough to be held in the palm of the hand and are intended for decoration as well as for miscellaneous use. Men hung the knives from their belts along with change purses and glass cases while women carried them in their purses or attached them to Maedeup pendants hung from their vest strings. Originally they were intended to be used in time of personal danger and especially for women to protest their chastity. Ornamental knives are made in the same way as other knives. They consist of a handle, blade and sheath. The handle and sheath are generally made of wood, ox horn, coral, gold or silver. When made of wood, a metal band, usually of silver or white brass is placed at the spot where the handle and the sheath join.

Blades are made of steel which is hardened by about 20 rounds of heating and pounding. After the blade is shaped it is inscribed with designs before a final heating and immersion in oil. Finally it is ground to sharpen the edge. The blade is then inserted into the handle and decorative pieces attached to the handle and sheath with bronze nail. Finally a silk string with decorative knots is tied to the sheath to complete the ornamentation. Although the shape has changed slightly from time to time, the knives are essentially the same today as in the past. The silver holder "Eunjangdo" was worn mostly by women of ranks as chest pendant and a symbol of their social standing. This dagger also served as a tool to save women from personal humiliation or peril, not by attacking an assailant but by killing themselves, under the moral obligation of medieval Korea 'to remain faithful to one's spouse'. Both the sheaths and blade handles, which ranged from gold and silver to jade, amber and ox horn, were meticulously decorated with fascinating designs.

Byeongpung

Some of Korea's loveliest art is embodied in the screens that were used by all classes of society in the past and are still a common household article. While some screens with certain motifs were used inside and outside the house on special occasions such as weddings, birthdays, ancestral rites and funerals, most were used to enhance the interior of the home with colorful decorations embodying auspicious symbolism and happy themes. They were set up in front of the windows to block drafts; hence the name Byeongpung, meaning "windbreak". Most Korean screen comes in eight panels.

Bamboo pipes

Traditional Korean pipes consist of a bamboo tube and a metal mouthpiece and bowl. The mouthpiece is usually made of brass, oxidized copper, jade, ivory or ox horn, however, the most common material is white brass often decorated with gold, silver or oxidized copper. The bowl is most often made of white brass, although plain brass and even porcelain are sometimes used. The metal bowls and mouthpieces of the bamboo pipes are generally pounded into shape.

Bows

Korean style bows are short and have a shooting range of 145 meters, while western bows are long and with 90 meters range. It takes about four months and many steps to make a Korean bow. The first step in making a bow is to cut the wood to the proper size. The wood is then bent into a circle by hearing it over a fire or boiling it in water and the ends tied with a string to prevent it from returning to its original shape. The curved wood is then dried in the shade for around two months. When the wood is sufficiently dried, pieces of mulberry wood are affixed to it with isinglass where the bowstring is to be attached and pieces of bamboo are affixed in the same way to the rest of the bow. Pieces of buffalo horn are glued to the outside of the bamboo and pieces of oak wood are affixed to the grip section. The next step is to affix cow tendons to the bow. To do this, the bamboo, which is normally 10mm thick, is shaved to a thickness of only 0.8 to 1 mm.

The cow tendon, which has been softened by beating it with a hammer, cut into 0.2-0.3mm thick pieces and washed with hot water to remove fat, and then is attached to the bow with isinglass. After seven to ten days, another layer of tendon is glued onto the bow and yet another layer is attached. The same process is repeated for five to six times. The bow is then left to dry for some 20 days at a temperature of 23 degrees Celsius and then it is placed inside a special drying room for another four weeks. The temperature inside the room increases gradually from 20 to 34 degrees. Once the bow is completely curved, notches for attaching the bowstring are cut at both ends of it. The bow is then balanced by trimming it on both sides. The "unstraining", as the trimming process is called, is repeated three or four times at an interval of two or three days. In such a way the bow is tailored to the physique, skill and posture of the person who will use it. Once the birch bark is attached, the bow is ready for stringing.

Totem pole (Jangseung)

Jangseung are tall wooden posts that used to stand at the edge of the village wearing fierce facial expressions. Their origination is not known but Sottae, a pole symbolizing a prayer for a good crop that marked an area believed to be ruled by spirits, is at the root of them. The purported functions of Jangseung are complex, though it was primarily to stand guard over the entire village and ensure the peace and prosperity of its inhabitants. They were simple wooden poles or stone pillars. Later, grotesque faces with fierce eyes were carved on them. With the human faces, the posts began to take on more complex significance. New posts were erected replacing the old ones in lunar leap months which occur early three years. Jangseung preparation process includes cutting down an appropriate tree, usually pine but sometimes chestnut or alder, and the carving and painting of the faces and raised all in the same day. Wooden Jangseung commonly exists in pairs. The inscription on them shows Great Generals of Everyone Under Heaven and Female Generals Underworld and were tutelary deities that guarded villages. Jangseung were from of folk belief, scattered around the country as guardians or even demarcation posts between two separate villages or temples. As an object of belief, they were scared and inviolable. Traditional Jangseung were supposed to look frightening given their role and symbolic meaning, and were often worn down and weather-beaten because they were placed outdoors because they were meant to ward off demons and guard villages. But, there is more to Jangseung than just that. Though their raised eyebrows and glaring eyes made them frightening, there was also a hint of humor in them. Jangseung were generally well taken care of as it was believed that the village would suffer from misfortune if Jangseung were to have any damage. And of course, it was taboo to cut down one. Some villages held periodic rites to honor the spirit of their Jangseung. During a grandiose ceremony, special foods would be placed on an altar before Jangseung and prayers offered to its spirit.

Brassware

Although there are varieties of brass depending on the metals and their mixing ratios to make alloys, basically brass is a copper-based non-ferric alloy. The Korean Brass in traditional sense commonly known as Yucheol is an alloy consisting 600g of copper and 168.7g of tin. Brassware was in wide use in Korean as late as the end of the Joseon period. A unique alloy, Korean brass was used to make objects essential for daily use including candlesticks, incense burners, wash basins, musical instruments and Buddhist ritual items. Bangja is a unique Korean method of making brass objects. First, an alloy of exact ratio of copper (78%) and tin (22%) is made. Then, it is heated and struck repeatedly into the desire objects. Bangja brassware is made by a team of 11 artisans who work systematically, it is hard to bend, break, discolor and gets glossy through prolonged use. The other method is by pouring molten brass in a fluid state into molds to produce many objects of the same size and type. Colors and quality of brassware differ according to quality and ratio of metal used for the alloy and aesthetic shapes of brassware depend on technical coomplishment.

Korean arts and craft culture portrayed through flowers

Patterns of nature have been used as a major motif worldwide as the intrinsic beauty that found in flowers is closely connected to human existence.

In particular, Koreans wished to enjoy their lives while being a part of nature and worshiping nature, so they devised meanings for each plant.

By incorporating each plant pattern endowed with such meanings into their daily life, they wished for wealth and happiness, while cultivating their virtue.

As the first flower to blossom in early spring, the apricot flower serves as a harbinger of spring as well as a symbol of beauty and fidelity. The lotus flower as a symbol of Buddhism and heaven as it remains its purity even in mud, and it includes a beautiful fragrance. Peony flowers symbolize wealth and prosperity due to their splendid beauty. Bamboos and chrysanthemums symbolize the fidelity and integrity of scholars, and orchids, which spread subtle scent in the deep forests symbolize fidelity. Peach and cotton are symbols of longevity. The patterns of these plants were often used in the daily lives of Korean people.

They also appreciated balloon flowers, cherry blossoms, hollyhocks, deva flowers, and rug rose and for their outstanding beauty and strong life forces.